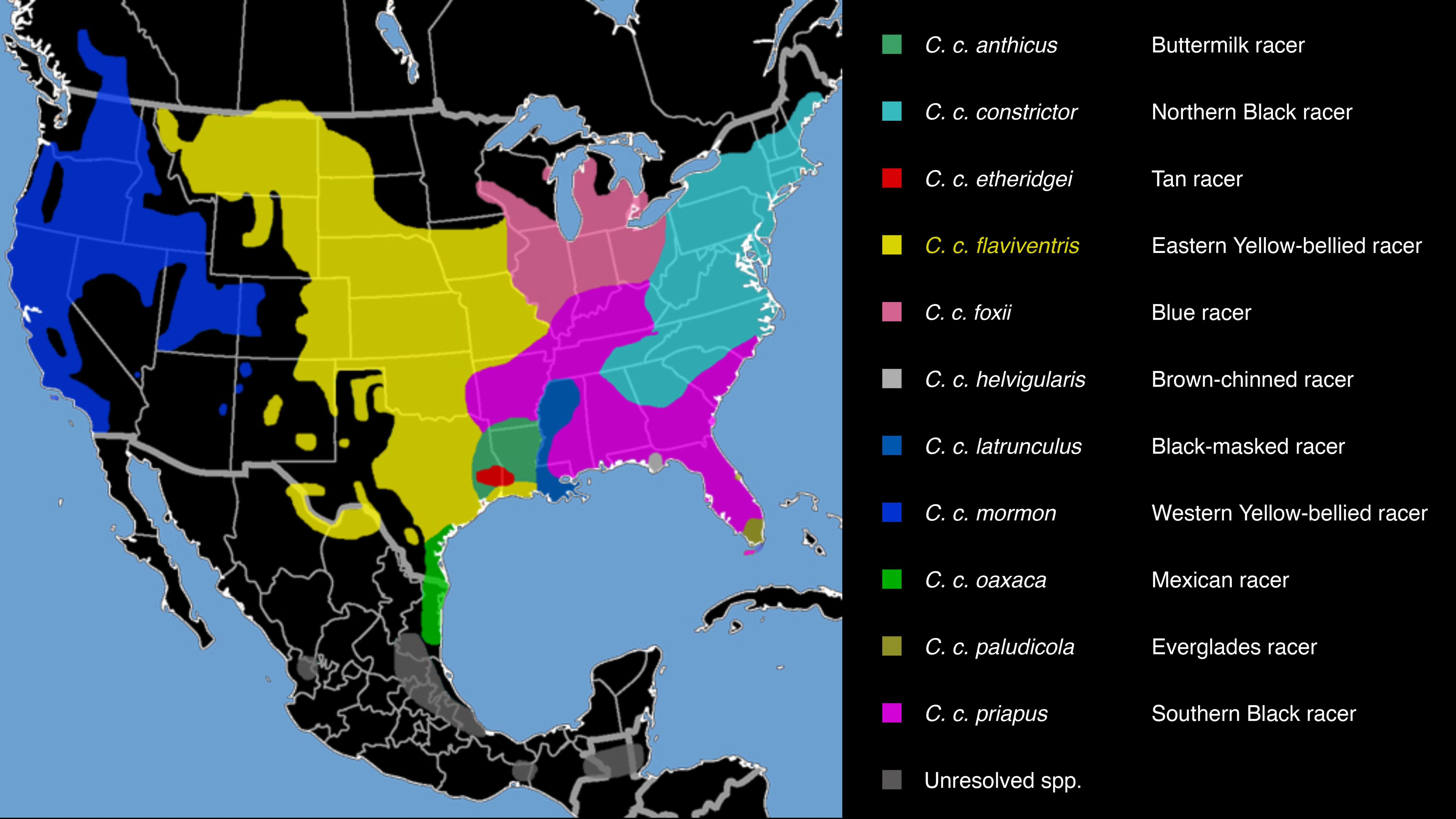

The eastern yellow-bellied racer (Coluber constrictor flaviventris) is a swift and slender species with keen eyesight for actively foraging during the day. From a distance they may seem entirely black with some light patches on the face, but they are a beautiful steel gray color with lateral blue accents and a bright underbelly. If you are lucky to peer closely into their eyes, the faint orange iris looks like a solar eclipse. Racers are found throughout North America, reaching northern latitudes in British Columbia and also south to Guatemala. There are 11 recognized subspecies that sport different color patterns, including speckled black and white, cryptic brown, yellow-green, light blue, and jet black. They are opportunistic predators and primarily feed on small mammals and insects, but there is dietary variation across their range. In eastern populations (e.g., eastern and western yellow bellies) 90% of the diet is made up by insects like grasshoppers and katydids, whereas for midwestern racers most prey are voles and mice. As is common in snakes, there is a dietary shift as they age, with larger individuals expanding their dietary breadth from small skinks and frogs to birds and other snakes.

When I caught this racer, it performed a few mock strikes before vibrating its tail rapidly against the substrate. Tail vibration in nonvenomous snakes is a widespread behavior, and though it certainly functions as an antipredator mechanism, its evolutionary story is not fully understood. The first hypothesis is that the sound of tail vibration mimics that produced by a rattlesnake rattle. The similarity would elicit a startle response in a predator, giving the prey a greater chance of escape. Under this scenario, tail vibration should be under stronger selection to resemble rattling in nonvenomous snake populations that co-occur with rattlesnakes. This is because predators in those areas are frequently exposed to rattlesnakes and have acquired avoidance behaviors in response to the warning signal. One case study on gopher snakes provides some support, with tail vibration becoming more prolonged, but still lacking any change in vibration rate or likelihood of initiating the behavior.

On the other hand, tail vibration may itself simply function as a warning, and rattlesnakes have evolved a more specialized form of the acoustic display. Then we would expect evolutionary history to strongly drive aspects of tail vibration broadly across snakes. In line with this rationale, snakes that do not have rattles and are more closely related to rattlesnakes tend to vibrate their tails more similarly in rate and duration. Thus far, it seems that tail vibration does not require a mimetic role to serve as defense, but the rattlesnake presence shapes tail vibration characteristics to enhance its effectiveness against predators.

Photographed after capture [5]