Feel free to get in touch with me via email about sharing my photography or to chat about natural history!

alephrocco9@gmail.com

Hello everyone and welcome to my natural history blog! My name is Christian Alessandro Perez-Martinez, and I am a biologist interested in the behavioral ecology and evolutionary morphology of reptiles and insects. Growing up in central Texas, I have always been driven by a love for observing animals in nature— anole lizards moving their eyes independently, click beetles launching into the air, and sphinx moths hovering with the utmost grace.

Since 2014, I have merged this interest with photography. Through my blog, I strive to convey the beauty and complexity of organismal biology and behavior, illustrating that we share this planet with life of all forms and functions. I hope that the narratives of my encounters and the ramblings of what I find fascinating instill curiosity and love for the natural world. We currently live in an era where the health of natural ecosystems is taking a backseat to human development. With this thought in mind, I hope that by becoming more intrigued and enamored with these critters (whose future hangs in the balance!!), we can all take steps to involve ourselves in conservation practices. Some actionable items include:

(1) changing habits in our daily lives (e.g., eat less meat! and be aware of what consumer products contain / where they come from),

(2) contributing to the process of legislative decision-making (vote and let your voice be heard by contacting your government representatives), and

(3) donating or involving ourselves with conservation efforts directly.

My first formal foray into evolutionary biology was during my freshman year at Harvard. I took a seminar on biological mimicry which introduced me to the astounding breadth of biological specimens and materials in the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ). A second course in entomology provided me with foundational knowledge, allowing me to contextualize my own personal discoveries in the wild. I felt at home learning from and collaborating with experts in a subject that I had always been enthralled by, and I never dreamed that many years down the road I would have explored diverse ecosystems in regions across the world.

By my first year, I had become a field assistant studying territoriality in Anolis lizards in Florida and later worked in the MCZ investigating convergent evolution in vine snakes. The following year, I traveled to the the Peruvian Amazon, where I held a second field assistant position to study the mechanisms of speciation in Heliconius butterflies. My love for tropical rainforests was ever increasing, and I soon after spent a semester abroad in Costa Rica through an OTS tropical biology program. My eyes became attuned to lizards, and I returned several times to La Selva Biological Station for my undergraduate thesis on the ecological morphology of anoles[1]. Since then, I have contributed towards work on Agalychnis tree frogs, including their natural history in the Osa peninsula[2] and mating behavior in the Caribbean versant.

Costa Rica represents a mix of the most heartwarming and intense experiences I have gone through in my journey as a person and naturalist. It is always a whirlwind of emotions when I visit Costa Rica, immersing myself with memories and creating new ones. Many years later, as an ode to the insects I hold so dear, I’ve written a book chapter on Costa Rican insects (available in the near future!).

Upon graduating with my bachelor’s degree in Integrative Biology, I traveled to Australia to study one of the most atypical and charismatic lizards: the frillneck lizard (Chlamydosaurus kingii), also called “frillies”. I examined the frill’s potential function as a deimatic signal[3] in the Northern Territory at Fogg Dam Conservation Reserve. The fieldwork was challenging. My study ran during the wet season with a monsoonal tropical climate, so sporadic localized lightning storms swept through the savannah woodlands almost every day. On foot, the lizards were nowhere to be found… frillnecks are cryptic agamids with acute visual and auditory senses, well-suited to circumventing avian predation. They would scurry around tree trunks and run up to the canopy well before I noticed them. After a week of HOT days but no frillies, I went out at night, and as luck would have it, I found them sleeping high up the trunks of eucalyptus trees.

Be sure to also check out an unexpected natural history observation[4] I made of a blind snake that vocalizes!! It was swept inside during the monsoons and had a lot on its mind to share with me. In the Kimberley, I also assisted on a project concerning movement patterns of the indomitable cane toad. Near the end of my time Down Under, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to travel to the Lesser Sundas. Finding blue pit vipers, swimming with manta rays, and of course, being in the presence of Komodo dragons— you’ll have to do some digging through my posts (scroll down the main page) to read about all the encounters! As an aside, my friends and I made observations of crab-eating frogs that make use of water buffalo dung as ideal microhabitats within an otherwise arid ecosystem[5].

The following year I found my way over to central Kenya, where I worked at Mpala Research Centre on projects that involved the whistling thorn acacia (Vachellia drepanolobium) and three of its ant mutualists. In one field experiment, we showed that in response to smoke, acacia seedlings appear to shift their nutrient allocation between plant structures[6]. This research is pertinent to fire ecology of the savanna biome.

It was eye-opening to traverse a landscape where megafauna dominate and species interactions were rather obvious. Elephants alter the landscape by knocking fever trees down to the ground, baboons scramble high up cliffs at sundown to take refuge from hyenas and lions, and multispecies assemblages of songbirds mob the occasional puff adder that lies dormant within the grasses. Below, I’ll leave you with a photo of me, Ivy, & Godfrey when we found a zebra mandible and giraffe skull, the latter with a dwarf gecko inside!

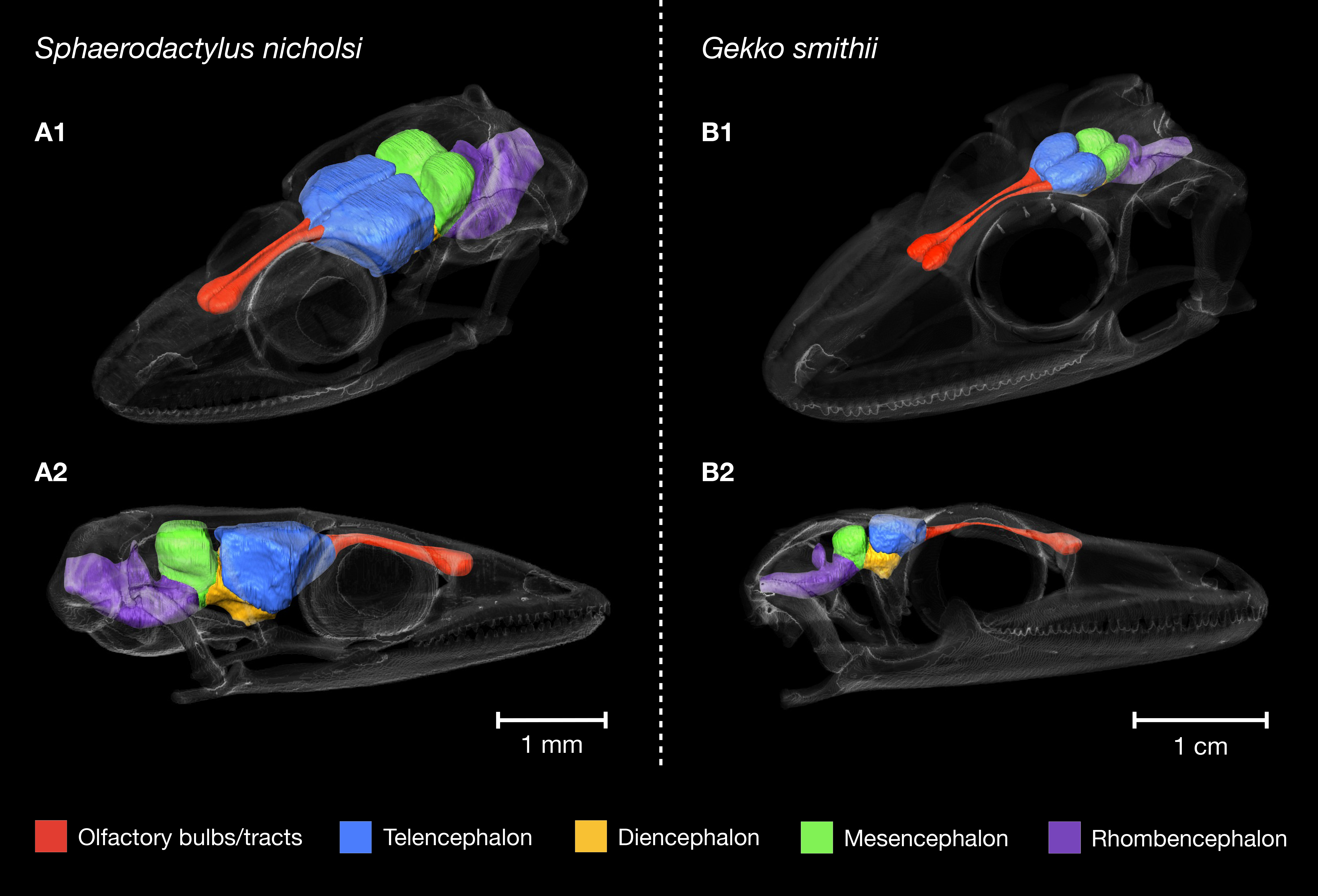

Currently, I am a graduate student in the Chipojo Lab at Mizzou. My research centers around the evolution of body size miniaturization in lizards and its implications for behavioral ecology, physiology, and neuroanatomy. So far, I have published a review[7] on miniaturization (see figures below), which discusses the phenomenon from a phylogenetic perspective and invokes physiological and anatomical constraints as drivers of ecological and morphological traits.

Within this framework, I am working with the Puerto Rican radiation of geckos in the genus Sphaerodactylus (also called sphaeros o salamanquitas), with a focus on the brain and metabolic rates. In two more projects, I have used substrate-borne vibrations as a passive monitoring methodology to reveal gecko activity patterns in situ and conducted behavioral experiments that examine social recognition in the lab. Legless lizards (Amphisbaenia) are also of interest within the realms of sensory ecology… Stay tuned in 2024 for updates!

Additional work I have contributed towards during my PhD include dewlap signal evolution[8] and neuronal densities in Anolis lizards[9]. A number of additional projects will soon be updated here once the publications become available.

I love your blog! Keep the excelente work like you always do ! My favorite scientist ! Love you so much. Mom

Sent from my iPhone

>

Hi Christian,

I was in Dr. Asgari’s ecology class a couple years ago. I remember you giving us a tour of the lizard room. Glad to see you’re keeping up the good work.